After delivering his state version of the Emancipation Proclamation, Andrew Johnson left his position as military governor of Tennessee to become Abraham Lincoln’s vice-president. He was replaced by another East Tennessean — William Gannaway Brownlow.

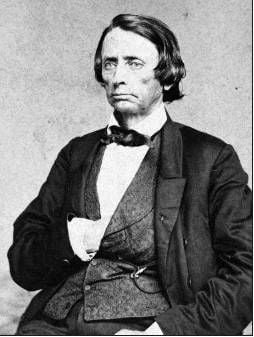

Brownlow, sometimes referred to as “Parson” Brownlow, was a radical Republican, a Methodist minister, journalist and a pain in the butt to anyone who favored the Confederate cause.

He started in journalism at the Elizabethton Republican and Manufacturer’s Advocate newspaper in 1838. There, he later started his own newspaper, sometimes called Brownlow’s Whig. It was known as the Whig due to his affiliation with that political party. There was no Republican Party at that time.

Brownlow later moved his paper to Jonesborough before moving it again, this time to Knoxville. At the start of the Civil War it was known as the Knoxville Whig and Rebel Ventilator.

For his anti-secessionist editorials and opposition to the cause, Brownlow was arrested by Confederate authorities, charged with treason and sent to jail. He was later released and deported to the North.

While in the North, Brownlow wrote a book detailing his time in Confederate captivity and engaged in a speaking tour, telling his story and selling his book.

When Union forces occupied Knoxville, Brownlow returned and resumed publication of his newspaper using the money from book sales.

Brownlow and Johnson were polar opposites. Brownlow, the Whig, regularly opposed Johnson, the Democrat, on every political issue in East Tennessee. They even ran against each other for public office.

The only thing the two ever agreed on was their opposition to Tennessee secession.

Brownlow immediately set to work restoring Tennessee to the Union, starting with the 13th Amendment to the U.S. constitution.

The 13th Amendment reads in part, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

Tennessee ratified the amendment on April 7, 1865, only eight days before the death of President Abraham Lincoln.

Then came the 14th Amendment, which in part reads, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Saying “a loyal Negro was more deserving than a disloyal white man,” Brownlow put his support behind the 14th amendment. But the fact it would grant citizenship to the now former slaves was too much for Tennessee Democrats.

In order to prevent a vote for the amendment’s ratification in Tennessee, Democrats attempted to leave Nashville so there would be no quorum in the legislature and thus no vote.

Brownlow got wind of their actions and ordered the arrest of enough Democrats to make a quorum and jailed them in the Capitol building. Therefore, they were listed as present but not voting.

Thanks to the efforts of Brownlow, on July 18, 1866, Tennessee became the first slave state and the third state overall to ratify the 14th Amendment granting citizenship to Blacks. Only Connecticut and New Hampshire ratified it more quickly.

Because Tennessee ratified both amendments quickly, it became the first Confederate state restored to the Union.

An interesting side note: New Jersey was the next state to ratify the 14th Amendment but then rescinded ratification. That Northern state would not re-ratify the amendment granting blacks citizenship until March 12, 2003.

Brownlow was elected to a second term as governor and continued to fight for the rights of black Americans.

He organized the Tennessee State Militia to do battle with the Ku Klux Klan. He even went as far as to ask newly elected President Ulysses S. Grant to station troops in counties with Klan activity.

At the end of his second term as governor, Brownlow was elected to the U.S. Senate, where he would help push through the Civil Rights act of 1870. This would in part give Grant the power to send soldiers to polling places to ensure that the rights of black voters was not infringed upon.

He later lent his support to the Civil Rights act of 1871, which allowed the president to suspend the writ of habeas corpus in order to deal with the Ku Klux Klan and various other white supremacy groups.

When Brownlow’s term in the Senate ended in 1875, he returned home to Knoxville and in 1876 purchased an interest in a newspaper there. In December of that year, he spoke at the opening of Knoxville College, established for black Americans.

Four months later, Brownlow died. He was buried in Knoxville’s Old Gray Cemetery.

Oliver Perry Temple, who served with Brownlow at the 1861 Greeneville convention against secession, wrote, “It was easy for friends to persuade Mr. Brownlow to do anything that did not violate his sense of right; to force him was impossible. A child could lead him; a giant could not drive him. When his mind was once made up, it was as immovable as the mountains.”

Ned Jilton II is a page designer and photographer for the Times News as well as the writer of the “Marching with the 19th” Civil War series. You can contact him at njilton@timesnews.net .